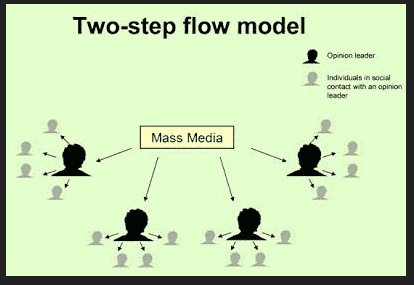

What is Media Audience theories? Audience theories have been of crucial importance for the way mediated communication has been understood since the first modern communication theories were formulated almost a century ago. They have followed the changing scientific climates and successive intellectual fashions in the social sciences and humanities, affecting both the different ways in which communication processes have been conceptualized and the ways in which succeeding scholarly traditions have researched them. In recent years, the concept of audience has been put into question as the emerging digital, interactive media appear to be blurring the deep rooted distinction between media production and media consumption that has characterized the era of mass media. The main theoretical difficulty with the concept of audience is that it is a single term applied to an increasingly diverse and complex reality. The term has thus come to comprise many shades of meaning gathered around a common core. This core denotes a group of people being addressed by and paying attention to a communication message that someone is producing and intending for them to perceive, experience, and respond to in one way or another. The range of meanings for audience includes, on one hand, the idea of a group of spectators gathered in the same physical location for a performance of some kind on which their attention is focused. On the other hand, an audience can be the dispersed, anonymous individuals who in the privacy of their home attend simultaneously or with a time delay to the content offered by a particular mass medium. Another distinction within the concept of audience has to do with the power distribution between the content producers and the users of mediated content. Media can be divided into three types, according to Jan Bordewijk and Ben Van Kaam. Until the 1980s, the audiences of classic transmis-sion media such as radio and television had control over neither content production nor reception: They could be reached only when the broadcasters chose to transmit centrally produced messages to them, which they then passively consumed. The audiences of consultation media such as print, on the other hand, actively choose when to access the centrally provided content and what content to access. Finally, conversational media rely on a communicative relationship characterized by the genuine, dialogical coproduction of meaning in which the roles of sender and recipient alternate. Another definitional question is whether audiences are a politically active public or a more passive and private group. A public in this connection has been defined as a collectivity mobilized by independently existing cultural or political forces (such as a political party or a cultural interest group) and being served by media provided by this public for itself. More traditionally, audiences have been regarded as a domestic, passive, and politically impotent collectivity, totally defined by and dependent on media provisions, often of an entertainment-oriented nature. However, as a consequence of the increasing “mediatization” of all aspects of modern life and the undeniable participatory qualities of the culture of media convergence, the American scholar Henry Jenkins and many others have proposed that the binary opposition of audiences and publics should give way to a conceptualization that recognizes their potential interdependence.These identifiable audience definitions have been identified with various successive scientific paradigms in the social sciences and humanities. This entry summarizes several of the most important of these. The Hypodermic Needle Theory The first audience theory that gained large-scale importance was metaphorically labeled the theory of media as a hypodermic needle. It not only was a product of the ruling behaviorist scientific climate in the 1920s and 1930s but also sprang from contemporary political and cultural concerns. According to the hypodermic theory, a mediated message could be seen as something injected under the skin of the recipient. Media effects were thus seen as direct, immediate, and strong. The emergence of this theory was a direct consequence of the emergence of the new broadcasting technology of radio, which made it possible for the first time to simultaneously reach the ears of all consumers and citizens in a nation. The Nazi leaders’ use of radio for blatant propaganda purposes, as well as the more democratically motivated use by U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt of radio addresses to the nation, gave rise to widespread concern that it would become possible for those in power to transform the citizens into mere puppets. At the same time, the hypodermic needle theory was inspired by influential sociological theories that the modern mass-society individual was lonely, vulnerable, and easily manipulated. The critical/cultural theories of the Frankfurt School were also influential; these scholars argued that the new cultural industries were functioning under a capitalist logic that would ideologically seduce and deceive the subordinate classes, through fascinating but mindless entertainment, into accepting conditions that would impoverish their life opportunities. This notion of defenceless audiences has continued, though in less crude form, to influence the understanding of processes of mediated persuasion as many advertising and public information campaigns are still based on a strategy that seeks to change the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of individuals by exposing them repeatedly to mass communicated stimuli. Similarly, this understanding of audiences also continues to frame widespread concerns over the effects of violent visual representations in television and computer game fictions on the vulnerable minds of children and young people. While the label hypodermic needle is extremely evocative, Everett Rogers and Roger Storey have admonished us that it is actually a label applied after the fact to capture the widely shared understanding of audience processes to which scholars were constructing an alternative. This alternative has become known as the two-step model of communication. The Two-Step Flow Theory The two-step flow theory arose out of some large-scale empirical studies in the United States in the 1940s, conducted by a team of researchers directed by the exiled Austrian scholar Paul Lazarsfeld, who found that both consumers’ choice of products and voters’ choice of politicians depended more on their interpersonal relations to significant others in their networks of family and friends than on their direct exposure to mass-mediated commercial or political messages. A campaign was thus found to influence its audiences as a result of the complex interrelations between a mass-mediated endeavor and the subsequent interpersonal process in which the campaign message got talked about in human networks. The label two-step flow was adopted because the studies found that the mass-mediated message would, as a first step, reach individuals with above-average prominence in their community—so-called opinion leaders. If the message succeeded in passing these gatekeepers’ filters of relevance and importance, they would then spread the message to more dependent individuals in their immediate surroundings (second step). This theory was supported by the fact that mass-mediated campaigns often were found to have minimal and indirect effects. The two-step flow theory, while encapsulating a fundamental truth about the communicative conditions of processes of social change, has been criticized for conceptualizing these processes in a much too mechanistic manner. Sven Windahl and Benno Signitzer have argued that we should rather see mediated processes of influence in terms of a multistep model of communication. It is possible to see Everett Rogers’s immensely influential theory of the diffusion of innovations to different groups of audiences (divided into innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards, depending on the speed with which they are likely to adopt innovations, both in the form of new products and in the form of new ideas) as such a more developed theory. Another alternative suggests the emergence of viral communication, in which the overly mechanistic idea of steps is abandoned altogether. Here, the channels through which communication spreads will have to be represented in a sophisticated model of intersecting personal networks, existing in the sea of discourses of the “mediatized” society. Uses-and-Gratifications Theory The next milestone theory of audiences, uses-and-gratifications theory, takes audience empowerment one step further by exploring what people do with the media. The key idea of uses-and-gratifications theory is that the uses that audiences make of the media and the gratifications produced by those uses can be traced back to a constellation of individual psychological and social needs. Elihu Katz, Jay Blumler, and Michael Gurevitch, three of the founding fathers of the theory, described how its 7-point platform wishes to account for how (1) the social and psychological origins of (2) needs generate (3) expectations of (4) the mass media or other sources, which lead to (5) differential patterns of exposure to the media, resulting in (6) need gratification and (7) other consequences. The media-oriented needs were typically described as the needs for information, relaxation, companionship, diversion, and escape, and the gratifications were characterized in identical terms—a practice that some uses-and-gratifications practitioners themselves acknowledge to be somewhat circular. Among the basic assumptions of the theory was the idea that both media and content choice are consciously and rationally made and directed toward quite specific goals and satisfactions and that individual utility is more important for media consumption than are values springing from familial or peer group rituals. Audience Reception Theories Reception research focuses on the ways in which audience members make sense of mediated meanings. It thus deviates from the mechanistic notion that media messages are merely transmitted to an audience whose understanding of those messages is unproblematic, and it insists that the audience’s actualization of mediated meanings must be the object of empirical investigation. Methodologically, reception research has, until recently, adhered rather strongly to the doctrinaire view that only qualitative methods such as depth interviews and ethnographic observation are suitable tools for such exploration. Reception research is explicitly interdisciplinary and—unlike the previous theories, which are based exclusively in the social sciences—attempts to cross-fertilize scholarship from the social sciences and the humanities. In a catchphrase, it has been claimed that reception research takes its theory from the humanities and its method from the social sciences. The theoretical platform thus comprises meaning oriented theories with hermeneutic origins, such as semiotics and discourse theories, whereas the methodological platform is constituted by fieldwork methods developed within the social sciences. The pioneering practitioners can be characterized as renegades from these two backgrounds who were dissatisfied with the prescribed practices of the parent disciplines: Researchers from the humanities were revolting against analyses in which claims about ideological effects on audiences were made on the basis of inferences drawn from textual analysis. Social science scholars were escaping from the straitjacket of quantitative methodologies and the way in which those methodologies had narrowed notions of what aspects of the audience were researchable at all. More specifically, in its early years, reception theory was trying to demonstrate that audiences were semiotically active in their encounter with mediated meanings, as opposed to the widely held view that media consumption, especially television viewing, was a passive, almost soporific condition. Reception theory’s fundamental reconceptualization of audiences was strongly indebted to the British cultural studies scholar Stuart Hall’s seminal theory of the meaning-making complementarity of the encoding and decoding moments of media production and the notion that there was no natural fit between these two moments. In other words, audience members had a relative freedom to interpret the encoded meanings offered to them in the media text, which was consequently regarded as polysemous (i.e., carrying many potential meanings). Among the handful of inspiring, lasting concepts proposed by Hall were also the notion of the text’s preferred meaning, or reading, and the three basic ways in which audiences could actualize this preferred meaning. Hall suggested that in the midst of textual polysemy, one meaning would nevertheless hold a privileged position. Since the mass media were firmly lodged within the capitalist social order and therefore logically served the hegemonic interest of the ruling classes, the preferred meaning would be one that conformed to this ideological interest. Continuing this logic of Marxist cultural theory, the class-divided audiences could actualize the encoded preferred meaning from one of three decoding positions: They could follow a dominant reading, in which they conformed to and took over, so to speak, the preferred meaning (for example, agreeing with a news report in which the government urged workers to show wage restraint for the sake of the country); alternatively, they could follow an oppositional reading, in which they would contest the ideological implications of the preferred meaning (for example, refusing to comply with the news report about the need for wage restraint); or they could follow the third option of applying a negotiated reading, which would lie somewhere between the two extremes (e.g., agreeing in overall terms with the news report’s recommended wage restraint but seeing many good reasons to divert from wage restraint in the case of specific social groups). The particular reading chosen by different audiences would depend on their life circumstances, often corresponding to social class position, and on the specific socio-culturally anchored interpretive repertoires at their disposal for decoding the media. The specific interpretive repertoires mobilized would also depend on the situational context in which decoding took place. For example, the specific decoding of a Hollywood movie by a teenage youngster would depend heavily on whether the movie was watched in the cinema with a group of peers or in front of the family screen with Mom and Dad. The need to explore such social uses of the media empirically was especially pioneered by the American audience ethnographer James Lull in a series of studies of family television. Finally, empirical fieldwork on audience meaning-making would also lean on the notion of interpretive communities, a concept originating in German and American reception aesthetics based in literary studies. The concept serves to express two different phenomena: first, the idea that the readings of media messages are likely to some extent to follow socio-demographic boundaries of age, gender, ethnicity, and so forth, which may thus be seen as a community in a loose sense of the term (e.g., a music video being read differently by White and African American youth); second, the phenomenon of fan cultures, in which members have a strong sense of cultural belonging to a cultural public, with something approaching membership. The concepts described here have been heavily discussed and contested in the reception theory literature since the 1980s. Therefore today they have become to some extent divested of some of their original, often Marxist, shades of meaning and have assumed the role of more general stock of the trade. This reinterpretation of theoretical concepts has been inspired by a move toward a more holistic conceptualization of audiences within the larger context of the communication process as a whole and away from the compartmentalized research endeavors of the 20th century. The drive toward holism in audience research (as defined by British sociologist David Deacon and his colleagues) is theoretically anchored in the social-constructionist turn in the human sciences, according to which the inter-discursive dimensions of media production and consumption have become a key condition of the mediatized culture. This theoretical development precedes the emergence of the culture of convergence, which in turn has served to corroborate the view that the distinction between media production and consumption is being elided. Theories of Collective Creativity The new digital media enable participation on an unprecedented scale. Individuals may participate in the digital, interactive media proper (the Internet, the World Wide Web, Web 2.0), but because all the old media, such as television and newspapers, have been transformed by digitalization into the complex of convergence culture, media users now have opportunities for participating in almost any encounter with any media. This participation includes all three modes of engagement with the media listed at the beginning of this entry: transmission, consultation, and conversation. As yet there is no full-fledged theory of the participating audience; we have only a rich array of promising theoretical fragments that together make up an incomplete mosaic of this audience. It has been proposed that we may be moving into the age of “disappearing audience,” but as U.S. scholar Henry Jenkins, one of the key analysts of convergence culture, warns, it is important that convergence raptures do not mislead us into believing that soon there will be no audiences, only participants. What we have to take into account in our thinking about audiences of the future is that convergence has to do with the following transformations: 1. The flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between multiple media industries, and the migratory behavior of media audiences 2. The emergence of a participatory culture, in which media producers and consumers no longer occupy separate roles but become participants who interact with each other according to a new set of logics 3. The development of collective intelligence, when consumer-participants pool their resources and combine their skills in realms where no traditional expertise exists Since, as Jenkins has admonished us, convergence refers to a process, not an end point, scholars interested in audiences must continue to devote their energies and resources to the building of new theoretical frameworks that enable us to grasp the thoroughly transformed conditions of audiences. The Scholar’s Life in the Habitat of Audience Theories When the history of audience theories is seen in an evolutionary perspective, as has been done here, it is important to realize that the Darwinian metaphor has its limits: It is not the case that the theories that first appeared in the habitat of audience theories have now become obsolete or even extinct. They continue to live their life, but not “as usual.” Time and again, as new animals have appeared, the older inhabitants have had to adapt to the influence of the newcomers, and they may have moved down in the struggle for dominance. Therefore, in audience theory today, all the traditions outlined above are still with us, although in mutually modified forms, and they offer themselves for the qualified judgment of new scholars entering the field. Kim Christian Schrøder Further Readings Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press. Jensen, K. B., & Rosengren, K. E. (1990). Five traditions in search of the audience. European Journal of Communication, 5, 207–238. Livingstone, S. (Ed.). (2005). Audiences and publics: When cultural engagement matters for the public sphere. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books. McQuail, D. (2005). McQuail’s mass communication theory (5th ed.). London: Sage. Rogers, E. M., & Storey, J. D. (1987). Communication campaigns. In C. R. Berger & S. H. Chaffee (Eds.), Handbook of communication science (pp. 817–846). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Schrøder, K., Drotner, K., Kline, S., & Murray, C. (2003). Researching audiences. London: Arnold. Windahl, S., & Signitzer, B. (1992). Using communication theory: An introduction to planned communication. London: Sage.

|

| Two Step theory |

COMMENTS